The University of Texas at Austin has a rich history in 3D printing, inventing one of the first forms of the technology, and now Texas Engineers have received a grant to tackle some of its most glaring problems.

In 3D printing, there is a tradeoff between the precision needed to create the object (resolution) and the speed and scale at which the object can be made (throughput). This is especially true at the nanoscale, where it is practically infeasible to make any kind of complex structure with multiple types of materials or patterns at a high rate.

The new $3 million grant from the National Science Foundation through the Future Manufacturing program will give a UT Austin research team - including Michael Baldea from the McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering, and core faculty at the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences - an opportunity to solve this problem at the nanoscale. And they say the technique they are developing will make it easier to produce more complex, tiny structures.

"As printing size gets smaller, printing rate goes down, and what we want to do is break that tradeoff," said Michael Cullinan, an associate professor in the Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering and leader of the project.

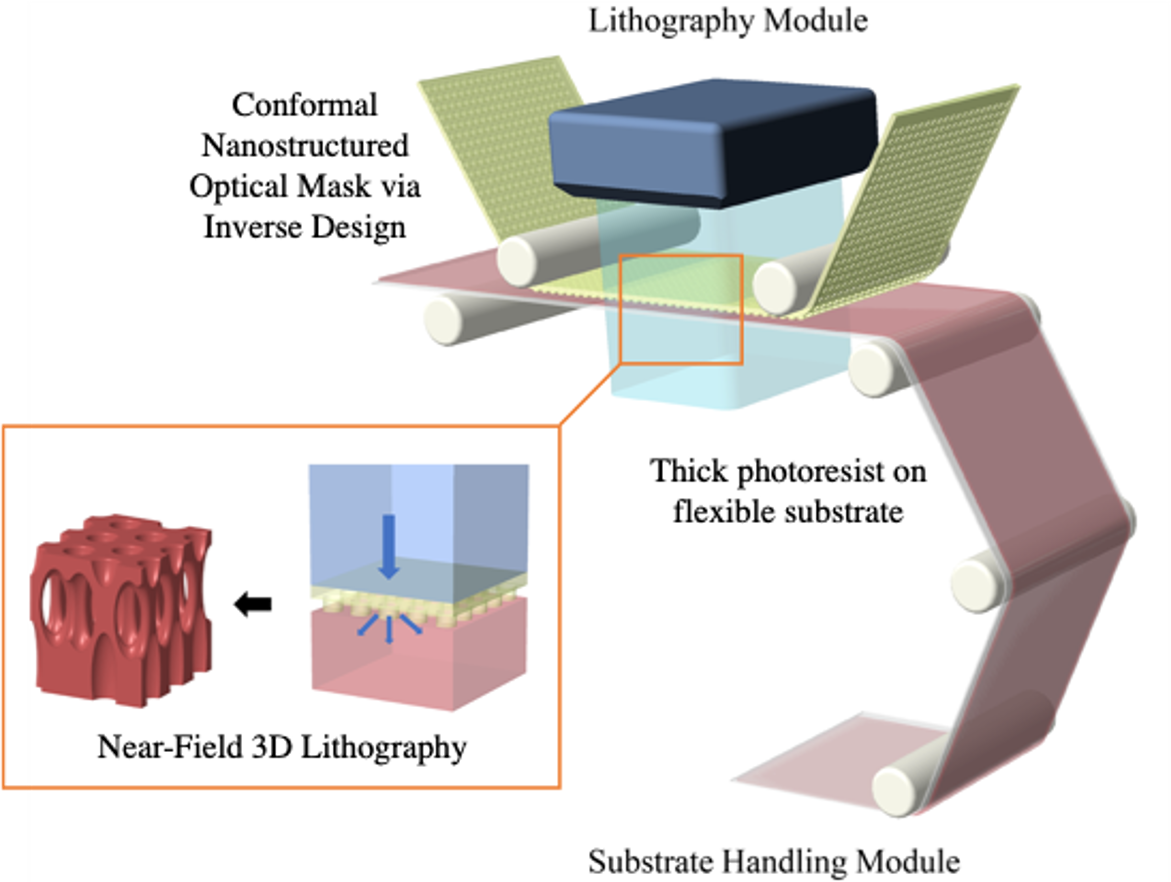

The Research: The standard process at smaller scales works by using light to cure a polymer material and change its properties. An image known as a mask is applied to the material to block the light from exposing and curing certain parts of that material, like a highly technological stencil. What is left under the mask is the 3D printed object.

At the nanoscale, the process of diffraction — where light can't fit through tiny holes and therefore veers off course — leads to inaccurate outcomes. The researchers are using this diffraction to their advantage to create patterns on their objects.

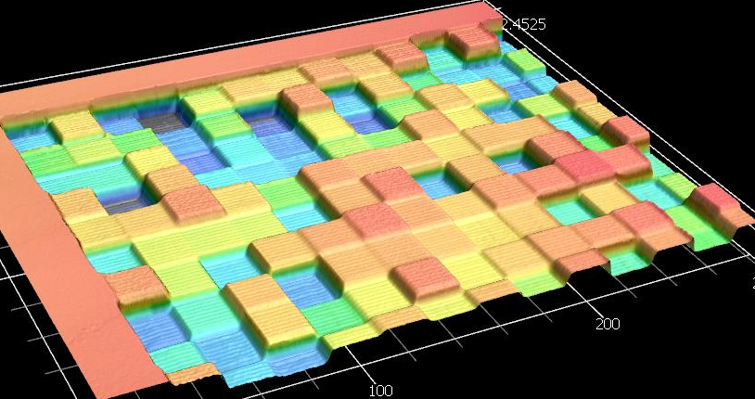

The researchers will use a different kind of lense that they call a metamask, placed much closer to the material than usual. Their process creates holograms — 3D images of light — with a thin structure. Exposing the photocurable material using holograms creates a solid 3D structure. Based on the color of the light, the material will react differently and take on different properties.

"You get an idea of what structure you want to build, and then work backwards to design the mask that forms the image needed to make that structure," Cullinan said.

This technique allows the researchers to build more precise images with improved resolution. That leads to the ability to create multi-material structures with increased speed because it can be done all at once instead of having to create multiple structures with different materials and then put them together in s serial fabrication process.