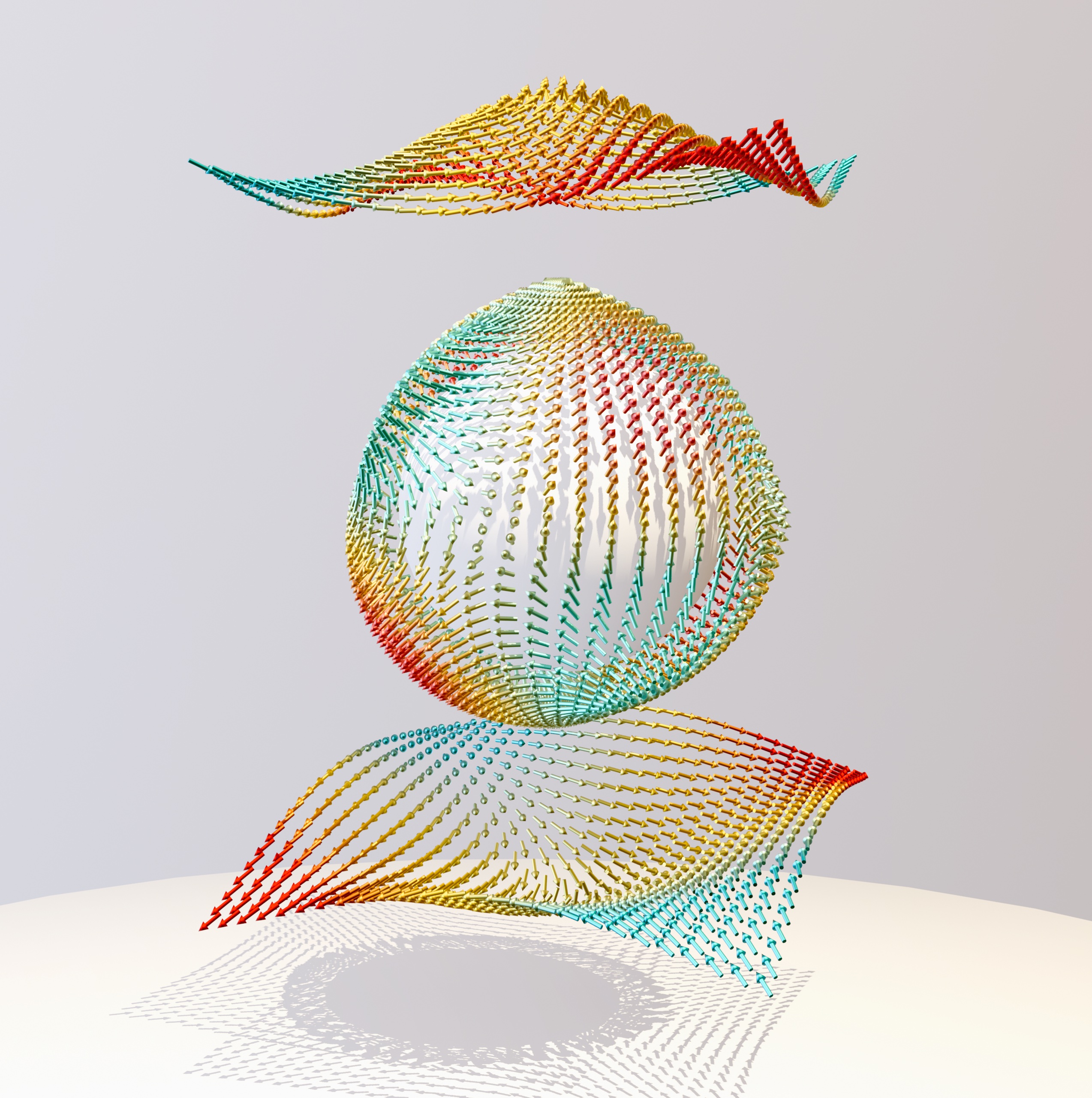

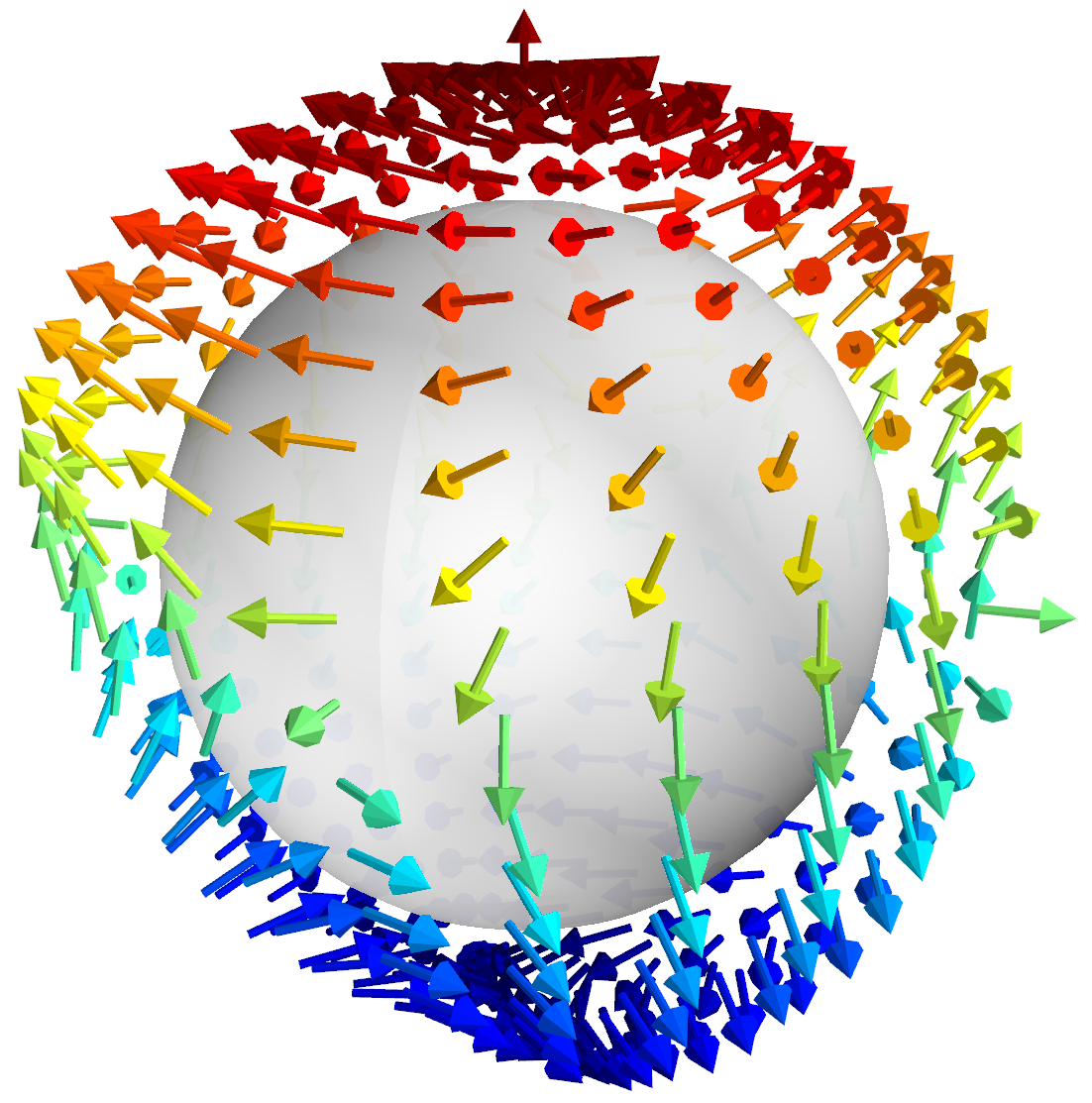

A new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), “Symmetry-protected topological polarons,” uncovers an unexpected layer of structure in one of the most common quasiparticles in solid-state physics: the polaron. The research shows that the atomic distortions surrounding an electron can form stable, symmetry-driven patterns, revealing an internal organization that had not been recognized before.

In everyday terms, this work reshapes how scientists understand the microscopic behavior of materials used in technologies like solar cells, LEDs, and electronic devices. Instead of behaving as simple, featureless objects, polarons can carry structured patterns that influence how energy and charge move through a material.

This discovery builds on earlier computational work from physics professor Feliciano Giustino’s research center. The previous research revealed vortex-like polarons in halide perovskites, a class of materials widely studied for solar cells and LED lighting. While that earlier research focused on a specific family of materials, the new PNAS study demonstrates that such symmetry-driven patterns are a general phenomenon, appearing across a broad range of crystalline solids.

The research team was led by Giustino, who directs the Center for Quantum Materials Engineering at the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences at The University of Texas at Austin. Additional Oden-affiliated co-authors on the paper include Kaifa Luo, Oden Institute graduate student, and Jon Lafuente-Bartolome, previously at the Oden Institute and who is now an assistant professor at the University of the Basque Country in Bilbao, Spain.