Feature

Published Dec. 8, 2014

The flow of the Antarctic ice sheet from the continent into the sea is projected to be the biggest factor in sea level rise this century—a change that could flood hundreds of cities around the world, depending on the extent of ice sheet collapse due to global warming.

Teasing out the probable ice sheet collapse scenarios from possible ones is a major focus for climate scientists around the world. But a hole in the research is proving to be a serious roadblock in this effort: being able to quantify uncertainty in predictions of ice sheet flow models.

It’s a point acknowledged by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the leading international body on assessing climate change, with a passage in their 2014 report reading:

“Abrupt and irreversible ice loss from the Antarctic ice sheet is possible, but current evidence and understanding is insufficient to make a quantitative assessment.”

Quantifying uncertainty in models is a hallmark of good science; since some level of uncertainty is present in all models, estimating just how much is important to understanding the reliability of the predictions of the models.However, quantifying uncertainty for Antarctic ice flow on the continental scale has been computationally prohibitive due to the size and complexity of the problem, says Tobin Isaac, a graduate student in the ICES CSEM program.

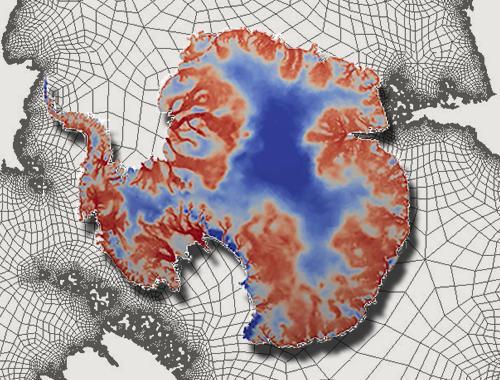

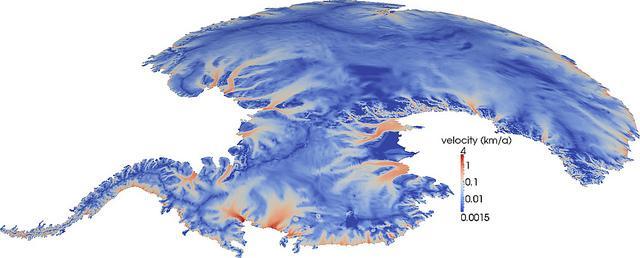

Isaac is working to tackle the problem by developing an algorithm that can infer information about ice flow deep below the surface of Antarctic ice, and quantify uncertainty of the computed values by solving a so-called inverse problem: given the observed data, work backwards to infer the unknown parameters in the model that would give rise to predictions that match the data. The key idea for overcoming the large-scale nature of the parameters is to recognize that the data provide only limited information about the model parameters, said Isaac, and to create algorithms that can extract this information at a cost that is proportional to only the information content in the data—as opposed to the data or parameter dimension. Accounting for these factors allows the inverse problem to be solved on modern HPC systems.

“The goal is that the number of steps the algorithm takes to get a good enough solution shouldn’t depend on your problem size,” Isaac said.

Isaac is the lead author of an article describing the algorithm that’s currently under review by The Journal of Computational Physics. His co-authors include his advisor Omar Ghattas, director of the ICES Center for Computational Geosciences and Optimization (CCGO); Noemi Petra, an assistant professor at The University of California, Merced; and George Stadler, an associate professor at New York University’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. Both Petra and Stadler are former ICES researchers.

Satellites have been recording Antarctic ice flow at the surface of the continent for decades. However, to understand the behavior at the top, one has to look at interactions happening deep below—on average two kilometers below—where the ice meets the rocky Antarctic continent. The friction between the continental rock and the ice, captured by a so-called “basal sliding coefficient” in the model, determines in large part if and how the ice moves, Isaac says.

“Gravity is always trying to pull the ice into the sea and the only thing holding it back is the ground beneath it,” Isaac said, “so how fast the ice is flowing on the surface depends on the basal sliding coefficients.”

Because of the ice sheet depth, friction can’t be measured directly. But, given satellite observations of ice flow velocities on the ice sheet’s top surface, it can be inferred solving the inverse problem, which reverse engineers the frication at the base of the ice sheet by examining the behavior of flow at the surface.

Solving the inverse problem is the first step of the algorithm and a highly intensive process in and of itself: both the inverse and forward problem are solved hundreds of thousands of times to compute the different friction values present across the Antarctic continent.

What comes next is identifying just how much these values can be trusted.

“You’d think ice is just ice, but there’s thousands of years of history hidden inside the ice,” Isaac said. “The possible things that can happen down where the ice meets the rock, it’s all so varied that it’s just impossible to hope to get any sort of measurement that would cover it all.”

However, scientists do have some prior knowledge and expectations about what the friction values between the ice and the rock are likely to be. Comparing these prior expectations with the calculated values, a method informed by Bayesian statistics, allows for the calculation of a distribution (called the posterior distribution) made up of the likelihood of various parameter values.

Finding the distribution enables researchers to see what level of uncertainty is associated with certain parameter combinations. The problem is, the math and computational power required to find the underlying distribution of so many values is extensive.

“While it’s simple to write out the definition of that posterior distribution, it’s very difficult to calculate and very expensive,” Isaac said.

A common method for elucidating the underlying distribution is to simply draw samples of the parameters using Monte Carlo methods, a technique that, like a naturalist surveying variation in a wild animal population, randomly samples the parameters that make up the posterior distribution until the distribution trend emerges.

However, it’s impossible to apply such a technique to the Antarctic model, says Isaac, because the amount of samples that would need to be drawn would take too much time to compute.

This inability to apply established uncertainty quantification methods to Antarctic ice sheet flow is what has kept the problem “on ice,” so to speak.

So, Isaac turned to a different method of drawing out the probability associated with various parameters. Instead of sampling the data, he developed a way to search through it. The algorithm involves simplifying the underlying posterior distribution into a Gaussian curve (a so-called “bell curve”) and then applying Newton’s method, a numerical analysis technique, to identify the most likely point within the entire distribution—the point that correlates with the “most probable” values for friction across Antarctica. By going through the vetting process, these values come with uncertainty attached.

“When we end up finding the most likely point, it’s a point that’s somewhat likely with respect to the prior knowledge, but also results in values that are somewhat likely based on the observation distribution,” Isaac said.

This approach based on Newton’s method has two qualities that make it useful for large-scale uncertainty estimation. The method is scalable because it disassociates the number of algorithmic steps from the size of the data, the main problem that has prevented other methods from being applied to large-scale problems. The method also learns about the local curvature of the original distribution—known as the Hessian—as it identifies the most likely point, and uses that curvature to when defining the simplified “bell curve,” so that the two distributions are well-matched.

Data that aids in the understanding of Antarctic ice flow will only grow in size. The algorithmic framework developed by Isaac will help make sure that it won’t outgrow the ability to compute its impact on ice sheet flow uncertainty quantification.

Isaac is quick to identify the algorithm as a framework for further research, rather than a ready-to-go research tool; there are still plenty of details to sort out before it could be used to inform a realistic model (a major one being finding a way to sample the true posterior distribution, instead of a Gaussian approximation, while keeping the computations tractable.)

But even as a work-in-progress, the model of Antarctic ice flow produced by the algorithm contained some notable features that could be a flag for further research, Isaac said. For example, some regions demonstrated little variability in the basal friction, while others were particularly prone to high levels of uncertainty.

“In particular, for our inverse problem we saw more uncertainty in our predictions in west Antarctica than in east Antarctica, which I certainty didn’t expect,” Isaac said.

But the biggest accomplishment of the code, and, according to Isaac, its primary purpose, is proving that by using new algorithms, problems deemed “intractable” can readily be solved.

“It’s no longer a question of if [quantifying uncertainty in Antarctic ice sheet models] can be done,” Isaac said. “What this paper shows is that it can be done. It will just take people getting together to get the correct forms for all these different terms and go into it.”

Isaac is collaborating with other researchers to improve the algorithm further by introducing additional data on the ice into the code. Don Blankenship, Ginny Catania, and Charles Jackson, researchers at UT’s Jackson School of Geosciences, are working on understanding how ice moved in the past by reconstructing ice layers below the Antarctic surface using radar. And Hongyu Zhu, a CSEM student, is working on revamping the inverse problem portion of the algorithm to include temperature data, an important ice-flow influencer.

However, as Isaac’s work demonstrates, finding a method to know what we don’t know about a simulation—the uncertainty—could be the most valuable contribution of all.

Stokes flow equations are a foundational part of Isaac’s algorithm. They characterize the viscous, “creeping” manner the Antarctic ice sheet moves across the continent. The way the equations fundamentally describe movement of viscous material makes them useful for a wide range of application. This happens to include heated rock as well as ice.

Isaac’s algorithm is a reengineered version of an algorithm that Stadler, Ghattas, and collaborators first developed to model convection of the mantle, a layer of the Earth that separates the surface crust from the inner core, and plays an important role in plate tectonics, earthquakes, volcanic action, mountain building, and other geological processes. Although made up of mostly solid rock, the mantle behaves as a viscous fluid over geological time scales, enabling Stokes equations to be used to describe its movement.

Isaac’s algorithm is a reengineered version of an algorithm that Stadler, Ghattas, and collaborators first developed to model convection of the mantle, a layer of the Earth that separates the surface crust from the inner core, and plays an important role in plate tectonics, earthquakes, volcanic action, mountain building, and other geological processes. Although made up of mostly solid rock, the mantle behaves as a viscous fluid over geological time scales, enabling Stokes equations to be used to describe its movement.

The mantle convection code was named “Rhea” after the legendary Greek titan associated with the concepts of “ground” and “flow.” In a nod to this naming convention, Isaac decided to name his version of the code “Ymir,” the mythological Norse frost-giant that was formed by the drips of thawing ice.

“It was a nice combination of the fire and ice coming from one code,” Isaac said.