Feature

Published Dec. 4, 2019

Oden Institute director leads effort to create virtual UAVs that can predict vehicle health, enable autonomous decision-making.

In the not too distant future, we can expect to see our skies filled with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) delivering packages, maybe even people, from location to location.

In such a world, there will also be a digital twin for each UAV in the fleet: a virtual model that will follow the UAV through its existence, evolving with time.

“It’s essential that UAVs monitor their structural health,” said Karen Willcox, director of the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences at The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin) and an expert in computational aerospace engineering. “And it’s essential that they make good decisions that result in good behavior.”

An invited speaker at the 2019 International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis (SC19), Willcox shared the details of a project — supported primarily by the U.S. Air Force program in Dynamic Data-Driven Application Systems (DDDAS) — to develop a predictive digital twin for a custom-built UAV. The project is a collaboration between UT Austin, MIT, Akselos, and Aurora Flight Sciences.

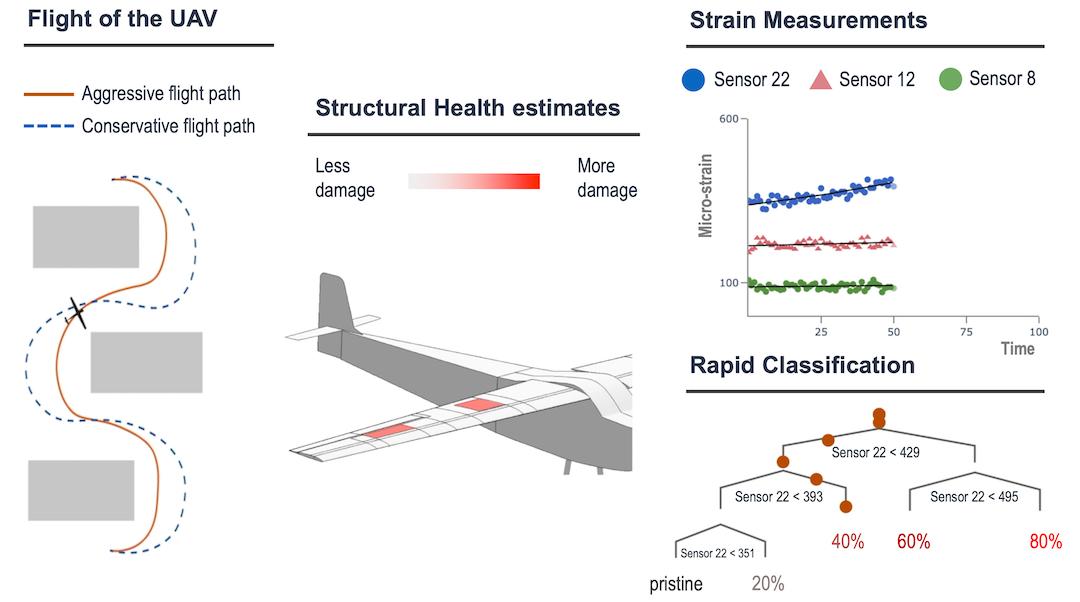

The twin represents each component of the UAV, as well as its integrated whole, using physics-based models that capture the details of its behavior from the fine-scale to the macro level. The twin also ingests on-board sensor data from the vehicle and integrates that information with the model to create real-time predictions of the health of the vehicle.

Is the UAV in danger of crashing? Should it change its planned route to minimize risks? With a predictive digital twin, these kinds of decisions can be made on the fly, to keep UAVs flying.

In her talk, Willcox shared the technological and algorithmic advances that allow a predictive digital twin to function effectively. She also shared her general philosophy for how “high-consequence” problems can be addressed throughout science and engineering.

“Big decisions need more than just big data,” she explained. “They need big models, too.”

This combination of physics-based models and big data is frequently called “scientific machine learning.” And while machine learning, by itself, has been successful in addressing some problems — like object identification, recommendation systems, and games like Go — more robust solutions are required for problems where getting the wrong answer may be incredibly costly, or have life-or-death consequences.

“These big problems are governed by complex multiscale, multi-physics phenomena,” Willcox said. “If we change the conditions a little, we can see drastically different behavior.”

In Willcox’s work, computational modeling is paired with machine learning to produce predictions that are reliable, and also explainable. Black box solutions are not good enough for high-consequence applications. Researchers (or doctors or engineers) need to know why a machine learning system settled on a certain result.

In the case of the digital twin UAV, Willcox’s system is able to capture and communicate the evolving changes in the health of the UAV. It can also explain what sensor readings are indicating declining health and driving the predictions.

The same pressures that require the use of physics-based models — the use of complex, high-dimensional models; the need for uncertainty quantification; the necessity of simulating all possible scenarios — also make the problem of creating predictive digital twins a computationally challenging one.

That’s where an approach called model reduction comes into play. Using a projection-based method they developed, Willcox and her collaborators can identify approximate models that are smaller, but somehow encode the most important dynamics, such that they can be used for predictions.

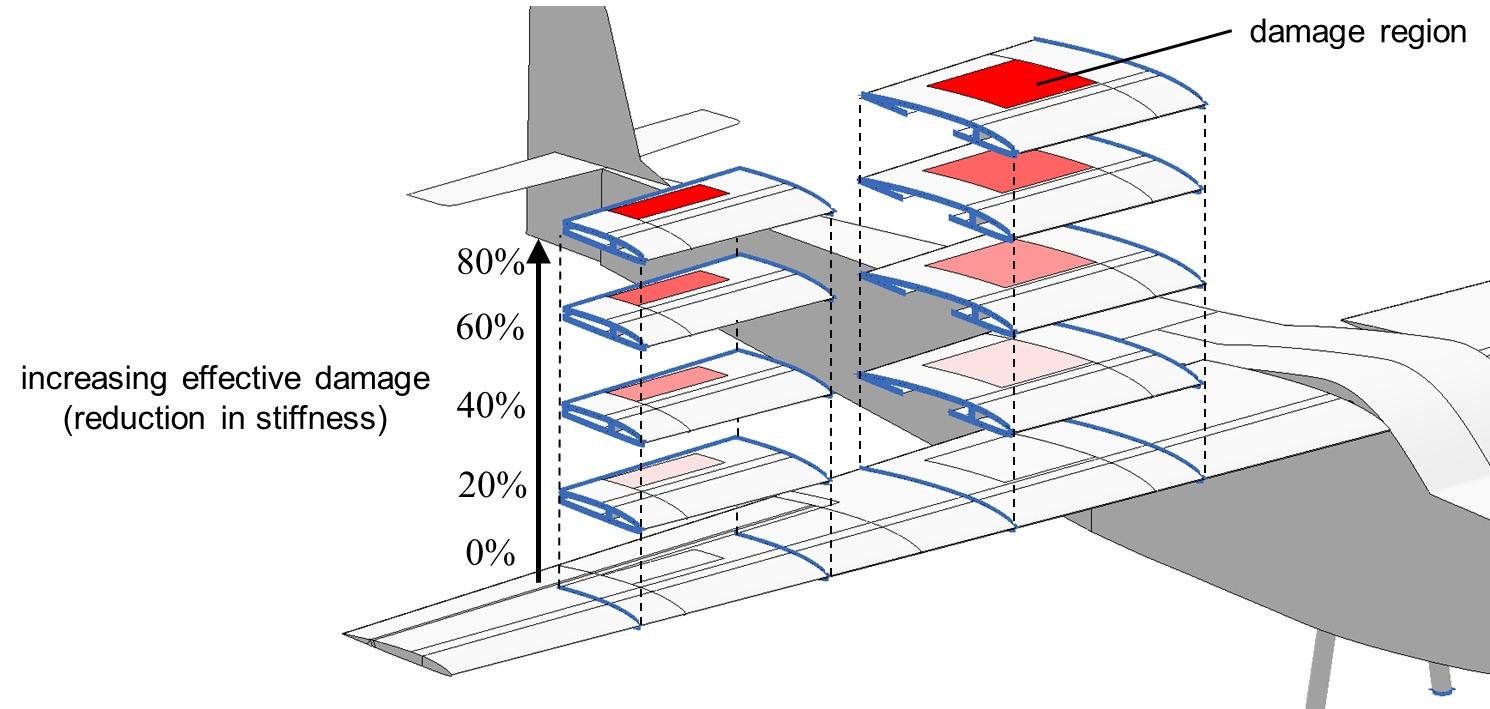

“This method allows the possibility of creating low-cost, physics-based models that enable predictive digital twins,” she said. Willcox had to develop another solution to model the complex physical interactions that occur on the UAV. Rather than simulate the entire vehicle as a whole, she works with Akselos to use their approach that breaks the model (in this case, the plane) into pieces — for example, a section of a wing — and computes the geometric parameters, material properties, and other important factors independently, while also accounting for interactions that occur when the whole plane is put together.

Each component is represented by partial differential equations and at high fidelity, finite element methods and a computational mesh are used to determine the impact of flight on each segment, generating physics-based training data that feeds into a machine learning classifier.

This training is computationally intensive, and in the future Willcox's team will collaborate with the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) at UT Austin to use supercomputing to generate even larger training sets that consider more complex flight scenarios. Once training is done, online classification can be done very rapidly.

Using these model reduction and decomposition methods, Willcox was able to achieve a 1,000-time speed up — cutting simulation times from hours or minutes to seconds — while maintaining the accuracy needed for decision-making.

“The method is highly interpretable,” she said. “I can go back and see what sensor is contributing to being classified into a state.” The process naturally lends itself to sensor selection and to determining where sensors need to be placed to capture details critical to the health and safety of the UAV.

In a demonstration Willcox showed at the conference, a UAV traversing an obstacle course was able to recognize its own declining health and chart a path that was more conservative to assure it made it back home safely. This is a test UAVs must pass for them to be deployed broadly in the future.

“The work presented by Dr. Karen Willcox is a great example of the application of the DDDAS paradigm, for improving modeling and instrumentation methods and creating real-time decision support systems with the accuracy of full-scale models,” said Frederica Darema, former Director of the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, who supported the research.

“Dr. Willcox’s work showed that the application of DDDAS creates the next generation of ‘digital twin’ environments and capabilities. Such advances have enormous impact for increased effectiveness of critical systems and services in the defense and civilian sectors.”

Digital twins aren’t the exclusive domain of UAVs; they’re increasingly being developed for manufacturing, oil refineries, and Formula 1 race cars. The technology was named one of Gartner’s Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends for 2017 and 2018.

“Digital twins are becoming a business imperative, covering the entire lifecycle of an asset or process and forming the foundation for connected products and services,” said Thomas Kaiser, SAP Senior Vice President of IoT, in a 2017 Forbes interview. “Companies that fail to respond will be left behind.”

With respect to predictive data science and the development of digital twins, Willcox says: “Learning from data through the lens of models is the only way to make intractable problems practical. It brings together the methods and the approaches from the fields of data science, machine learning, and computational science and engineering, and directs them at high-consequence applications.”